CHHSM Advocacy Center

Vol. 9: Mental Health and Substance Use

Niquanna’s Story

Image description: Headshot of Niquanna Barnett wearing glasses and a pink shirt.

“It is important for anyone working with minorities and other ethnic groups to have cultural competency, and knowledge of historical trauma is a significant part of that. Understanding historical trauma and microaggressions can also help with understanding the different cycles of emotions many African Americans are experiencing in conjunction with current societal events,” says Niquanna Barnett, an In-Home Family Therapist and Intake Specialist at CHHSM member organization Orion Family Services in Madison, WI. At the 2020 CHHSM Annual Gathering, Barnett presented a workshop entitled Historical Trauma: Understanding It, How to Heal, and Move Forward, which was overwhelmingly well received by the attendees and has garnered interest and attention since then. Barnett has several upcoming speaking engagements.

Historical Trauma, as defined by clinician and researcher Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, is the “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experience.” This multigenerational trauma often stems from atrocities committed against a particular group of people, such as slavery, genocidal colonization of Indigenous Peoples, the Holocaust, Japanese internment camps, eugenics campaigns, and forced migration. It is distinct in how it is shared by a community of people, rather than solely by an individual, and can affect members through trauma-related symptoms, like poor overall health, depression, substance use, and high rates of suicide, even though they were not present for the traumatic event(s). “On the simplest level, the concept of intergenerational trauma acknowledges that exposure to extremely adverse events impacts individuals to such a great extent that their offspring find themselves grappling with their parents’ post-traumatic state,” states pioneering researcher and professor Rachel Yehuda. The more provocative claim her research points to is how the effects of stress and trauma can transmit biologically through DNA from one generation to the next.

In her presentation, Barnett emphasizes how acknowledging and holding space for the history of an individual’s community needs to be present in the therapeutic process, as it impacts the way in which that client “moves through the world.” Psychologist Jennifer Mullan, in her work on decolonizing therapy, further explains that this approach more truly considers the whole person when their community’s experiences are included: “It's putting a focus on how trauma from oppression and the history of colonization has played a role in people's well-being and mental health. It’s realizing that we cannot just look at an individual without looking at what is happening systemically as well.” Doing so assists people to reweave and rewrite their personal narrative within the larger one and to begin to heal from a place of deeper truth. Such therapies may also include reclaiming and incorporating cultural traditions and healing practices into the process.

As People of Color remain disproportionally impacted by COVID-19, police brutality, and an array of current racist policies and inequities, we need to increase funding for culturally competent care and programs like minority fellowships and to remove all barriers to mental health treatment now more than ever.

Erica's Story

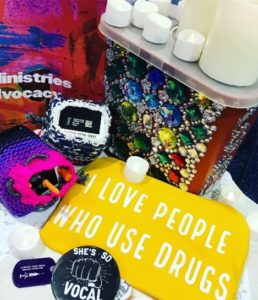

Image description: decorated needle receptacle and naloxone spray, candles, a yellow cloth that says ‘I love people who use drugs’ and other colorful ritual items.

“Congregations of healing shepherded by spiritual leaders—people with lived experience of drug use and overdose and their loved ones—have long been convening in the many margins of our society. Challenged to find spiritual community which calls us by name and welcomes us fully, we have grown our own community, often among the shadows, finding creative ways to stretch limbs to the light, to stimulate growth, to keep hope and one another alive,” says Erica M. Poellot, whose own experience with substance use grounds and guides her ministry. Poellot is a leader working at the intersections of harm reduction and spirituality. She is the Project Coordinator for the United Church of Christ’s Overdose and Drug Use Ministries (ODUM), the Director of Faith and Community Partnerships for the National Harm Reduction Coalition, and the Senior Ministry Innovator at Judson Memorial Church, a co-founding partner of Faith in Harm Reduction. “By virtue of visibility in these roles I have had the opportunity to listen into these spaces and have heard that there is a clear opportunity in this moment for both transformation and liberation.”

Image description: altar covered in white cloth with vase of flowers, candles, and items which say, ‘got naloxone?’ and ‘I love drug users.’

ODUM brings together pastors, lay leaders, theologians, people who use drugs, service providers, activists, and other collaborators in order to advocate for and increase the engagement of local churches in ministries with people who use drugs, people who have been affected by drug use, and people who may be at risk for or have experienced incidents of overdose. Poellot and her colleagues are architecting the way forward for faith communities to be co-builders in this life-saving work. Their ministry involves education, prevention methods and training, access to naloxone, and theological reflection and rituals—such as blessing naloxone and honoring those who have died. CHHSM staff is part of the ODUM working group and is seeking new ways of partnering together as ministries of healing and harm reduction.

Poellot’s education on overdose and drug use goes beyond discussing the tragic facts of the opioid overdose crisis, which accounted for 72,000 beloved lives lost in 2019, and how substance use and treatments work—which are included and important. She also calls us to challenge “the well-entrenched moral frameworks, orthodoxy of the disease and recovery models, the racist and classist core of the war on people who use drugs…the attachment of stigma, shame and sin to the drugs issue and the people who use them.” Poellot further names the necessary reframing from public health perspectives that should guide faith communities’ response. As articulated in the American Journal of Public Health: “The accepted wisdom about the US overdose crisis singles out prescribing as the causative vector. Although drug supply is a key factor, we posit that the crisis is fundamentally fueled by economic and social upheaval, its etiology closely linked to the role of opioids as a refuge from physical and psychological trauma, concentrated disadvantage, isolation, and hopelessness.”

These issues are matters of spirituality and justice. As such, the church could provide a vital place of hope and healing by engaging in this ministry and by following those who already are.

Definitions

Particularly coming from a social justice perspective, discussing mental health and substance use requires important distinctions in the language often used, and understanding the range of issues involved. To provide a foundation for this conversation, below are some helpful definitions from a variety of sources committed to this work.

- Mental Health: a state of wellbeing in which a person is aware of their own potential, is able to cope with the normal stresses of life, and can make a contribution to their community, as defined by the World Health Organization. Mental health is thus more than the absence of mental illness symptoms or diagnosis, but also encompasses experiencing joy and meaning from life. The WHO further explains that, “mental health promotion involves actions that improve psychological well-being. This may involve creating an environment that supports mental health. An environment that respects and protects basic civil, political, socio-economic and cultural rights is fundamental to mental health. Without the security and freedom provided by these rights, it is difficult to maintain a high level of mental health. National mental health policies should be concerned both with mental disorders and, with broader issues that promote mental health.”

The United Church of Christ has been advocating for mental health justice for decades, particularly through its Mental Health Network. - Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): “stressful or traumatic events that include, but are not limited to, maltreatment, parental incarceration, neighborhood violence, family violence, and parental instability, all of which have immediate and lasting disruptive effects on youths’ physiological development as well as their physical and mental health,” according to the American Psychological Association. ACEs have been linked to chronic health illness, mental illness, and substance use in adulthood. Children of color and low-income youth (0-17 years) experience disproportionately higher rates of ACEs. However, according to the CDC, ACEs can be prevented by enacting policies that support families and children economically, socially, and environmentally.

- Race-Based Traumatic Stress (RBTS): “refers to the mental and emotional injury caused by encounters with racial bias and ethnic discrimination, racism, and hate crimes. Any individual that has experienced an emotionally painful, sudden, and uncontrollable racist encounter is at risk of suffering from a race-based traumatic stress injury. In the U.S., Black, Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) are most vulnerable due to living under a system of white supremacy.

Experiences of race-based discrimination can have detrimental psychological impacts on individuals and their wider communities. In some individuals, prolonged incidents of racism can lead to symptoms like those experienced with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This can look like depression, anger, recurring thoughts of the event, physical reactions (e.g. headaches, chest pains, insomnia), hypervigilance, low self-esteem, and mentally distancing from the traumatic events. Some or all of these symptoms may be present in someone with RBTS and symptoms can look different across different cultural groups.

It is important to note that unlike PTSD, RBTS is not considered a mental health disorder. RBTS is a mental injury that can occur as the result of living within a racist system or experiencing events of racism.” – Mental Health America - Trauma Informed Care (TIC): “an approach in the human service field that assumes that an individual is more likely than not to have a history of trauma. Trauma-Informed Care recognizes the presence of trauma symptoms and acknowledges the role trauma may play in an individual’s life—including service staff…Trauma-Informed Care requires a system to make a paradigm shift from asking, “What is wrong with this person?” to “What has happened to this person?” The intention of Trauma-Informed Care is not to treat symptoms or issues related to sexual, physical or emotional abuse or any other form of trauma but rather to provide support services in a way that is accessible and appropriate to those who may have experienced trauma,” according to the University of Buffalo Center for Social Research. Similar therapeutic approaches that have stemmed from TIC include Social Justice Informed Mental Health Literacy and Healing Centered Engagement.

- Gender Affirming Therapy: “a therapeutic stance that focuses on affirming a patient’s gender identity and does not try to “repair” it,” according to the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Some interpretations of such care also include de-pathologizing transgender and gender-diverse people. Currently ‘gender dysphoria’ is diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Similar to how ‘homosexuality’ was defined as a psychiatric disorder up until 1973, after years of research conducted by Evelyn Hooker and protests against the APA gave way to needed change, advocates call for the APA to affirm gender diversity as a natural and healthy aspect of the human experience.

The United Church of Christ’s Our Whole Lives sexuality education program supports this care and names gender diversity as a natural part of the human experience, not an illness. - Prison Industrial Complex (PIC): a term used to “describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems. Through its reach and impact, the PIC helps and maintains the authority of people who get their power through racial, economic and other privileges. There are many ways this power is collected and maintained through the PIC, including creating mass media images that keep alive stereotypes of people of color, poor people, queer people, immigrants, youth, and other oppressed communities as criminal, delinquent, or deviant. This power is also maintained by earning huge profits for private companies that deal with prisons and police forces; helping earn political gains for “tough on crime” politicians; increasing the influence of prison guard and police unions; and eliminating social and political dissent by oppressed communities that make demands for self-determination and reorganization of power in the US.” – Critical Resistance

The United Church of Christ has condemned the PIC for decades, in particular through its 1997 General Synod resolution. - The War on Drugs: a campaign launched by former President Richard Nixon in 1971 which increased drug prohibition policies and criminalization of drug use, sale, and distribution under the guise of a public health effort. The consequences of these actions are magnified for communities of color, who are disproportionately targeted by law enforcement and face discriminatory practices across the justice system. This impact is not an accident, as the war on drugs is inherently racist and colonialist: “President Nixon waged the war on drugs in response to public demonstrations led by civil rights activists and Vietnam War opponents, pushing a narrative that linked black communities and protesters with drug use. John Ehrlichman, a prominent official in the Nixon White House, owned up to this agenda years later. “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black,” Ehrlichman said in an interview in 1994, “but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.” These harmful and unjust polices have worsened over the years and remain in place today. By 2017, more than 2.2 million Americans were in prison or jail, and nearly 60 percent were Black or Latinx. Black Americans are nearly six times more likely to be incarcerated for drug-related offenses than their white counterparts, despite equal substance usage rates.

Further, because criminalization of drug use has not been shown to lower drug use or to make communities healthier or safer, the war on drugs has created devastating results such as mass incarceration, proliferated violence in the US and throughout the world, family separation and instability, negative impact on employment and housing opportunities, and a decrease in funding for mental health services to name a few.

The United Church of Christ has spoken out against the war on drugs and named it as the New Jim Crow in its 2015 General Synod resolution. - Models of Drug Use: Throughout history people have tried to understand the concept of drug use and why some people become dependent or addicted to certain drugs and why others do not. Below is a selection of the variety of theories that have developed over time.

- Moral Model: A framework popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries which understood substance use as a sin a moral failing. Under the influence of this model, the response was to punish people who used substance including whippings, public beatings, fines, public ridicule, and incarceration.

- Disease Model: A medical viewpoint which perceives substance use disorder as a disease. Under this model, substance use does not occur on a spectrum, people are not able to control their intake of a given substance, and the disease can only be managed through abstinence and cannot be cured. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and many other 12 step programs are based on this model.

- Psycho-Dynamic Model: A theory originating with Sigmund Freud which connects difficult and/or traumatic experiences from childhood with a person’s ability to cope. Substance use may thus be an unconscious response to these life experiences in order to cope or self-medicate.

- Socio-Cultural Model: A framework that has come into popularity in recent years which focuses on society as a whole and not just individuals. It is based on the idea that the type of society in which people live has an impact on their drug use. In particular, this model makes links between inequality and drug use. It suggests that people who belong to groups who are culturally and socially disadvantaged are more likely to experience substance use problems. It also recognizes that society stigmatizes people who use drugs, exacerbating the problem. Because this model links substance abuse to the conditions of the wider society, the solution to “drug problems” revolves around changing the social environment, rather than treating individuals. This involves developing ways to address poverty, poor housing, discrimination, and the like.

- Public Health Model: An integrated approach grounded in examining the relationships between the characteristics and effects of a substance, the characteristics of the people who use substances, and the context or environment in which substance use occurs. It supports the philosophy of harm reduction and focuses efforts on reducing harms brought about by certain types of substance use instead of on eradicating substance use altogether.

- Harm Reduction: “refers to policies, programs and practices that aim to minimize negative health, social and legal impacts associated with drug use, drug policies and drug laws. Harm reduction is grounded in justice and human rights–it focuses on positive change and on working with people without judgement, coercion, discrimination, or requiring that they stop using drugs as a precondition of support.” Examples of harm reduction services include syringe access and disposal, naloxone, medication assisted treatment, supervised consumption sites, housing access, referrals, and healthcare access.

The United Church of Christ’s Overdose and Drug Use Ministries supports and uses this model. - Substance Use Spectrum: a framework that views substance use as occurring on a spectrum, “from total abstinence to chaotic use and a whole host of behaviors in between. There are many degrees of use, and the extent to which substance use affects or interferes with a person’s life varies by stance and by circumstance. While abstinence is a part of the substance use spectrum, harm reduction does not require it; instead, harm reduction espouses the goal of “any positive change,” including safer consumption of a drug even (and especially) in chaotic use,” according to Faith in Harm Reduction.

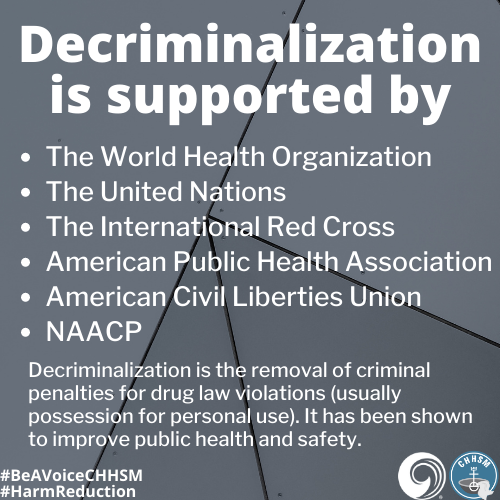

- Decriminalization: the removal of criminal penalties for drug law violations (usually possession for personal use). Because decriminalization has been shown to improve public health and safety, the United Nations and World Health Organization released a joint statement encouraging countries to review and repeal laws that criminalize drug use and possession of drugs for personal use. Examples of other organizations that support decriminalization include the International Red Cross, the American Public Health Association, American Civil Liberties Union, the NAACP and Latino Justice.

- Transformative Justice: “a liberatory approach to violence that seeks safety and accountability without relying on alienation, punishment, or state or systemic violence, including incarceration or policing…Individual justice and collective liberation are equally important, mutually supportive, and fundamentally intertwined—the achievement of one is impossible without the achievement of the other.” - generationFIVE.

- Pleasure Activism: “making justice and liberation the most pleasurable experiences we can have; learning that pleasure gets lost under the weight of oppression, and it is liberatory work to reclaim it,” according to adrienne marie brown. “Oppression makes us believe that pleasure is not something that we all have equal access to. One of the ways that we start doing the work of reclaiming our full selves—our whole liberated, free selves—is by reclaiming our access to pleasure.” The term was originally coined by harm reductionist Keith Cylar.

Background Information

Although there are many important issues to consider when discussing both mental health and substance use, we believe it is crucial to highlight two connecting points on these topics: trauma and the criminal justice system.

According to SAMHSA, a way of understanding psychological trauma is through the three E’s: the event, “a single incident or series of events involving an actual or extreme threat of harm;” the experience of the event in how one makes meaning of what happened; and the effects it has on a person, which may be immediate or surface long after the incident occurred. Traumatic events can be wide ranging, including childhood abuse, natural disasters and accidents, sexual violence, a challenging medical diagnosis, family separation, loss of a loved one, losing housing, experiences of oppression and discrimination, and viewing police brutality imagery or other violence, even if you were not physically present for the event. Trauma comes from the Greek word for “wound,” and thus illustrates the pain and lingering healing process a traumatic event can have on a person.

Some of the most common challenges people face after trauma include anxiety, re-experiencing the trauma, hypervigilance, avoidance, feelings of guilt and shame, grief, depression, changes in self-image and views of the world, and substance use. As noted in Erica’s story above, public health experts have made linkages to trauma, hopelessness, oppression, and isolation with the opioid epidemic. Understanding what pain(s) people are using substances to suppress must inform our advocacy work—and not just in isolation to this topic, but advocacy as a whole. In the words of Ruby Sales, we must ask, “where does it hurt?” and respond to the pain with systemic change.

According to research conducted on 24 countries, more than 70 percent of respondents reported experiencing a traumatic event in their lifetime. The US’s results match this overall figure and were ranked among the countries with the highest levels of traumatic events. Other data reveals further inequities in these numbers with tragic results. About 1 in 5 veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, and an average of 17 veterans die by suicide every day. American Indians and Alaska Natives have the highest rates of lifetime major depressive episodes of any ethnic or racial group, and suicide is the second leading cause of death for AI/AN aged 10-31. Transgender adults are nearly 12 times more likely to attempt suicide than the general population.

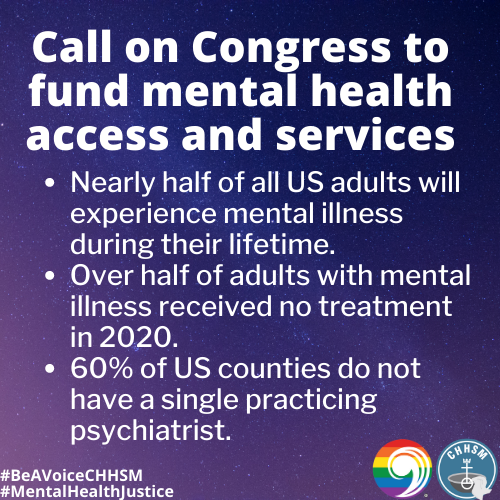

Despite this severity, access to insurance and to mental health providers remains a serious problem. Over 1 in 10 adults with mental illness had no insurance coverage in 2018 and 57.2% of adults with a mental illness received no treatment in 2020—which makes sense given that 60% of US counties do not have a single practicing psychiatrist. The Trevor Project’s national survey found that 46% of LGBTQIA youth reported they wanted counseling from a mental health professional but were unable to receive it in the past year. One of the more devastating illustrations of the access crisis is with parents who are forced to give up their parental rights in order for their child to receive mental health treatment. When insurance no longer covers expensive residential care and parents cannot afford the costs, they may have to choose to relinquish custody to the state’s child welfare agency, who will pay for the treatment—but only under this circumstance.

What is perhaps even more egregious than the barriers to access is that the largest mental health provider in the US is the incarceration system. Severe lack of funding and resources creates an environment in which those facing mental health challenges may engage in non-violent “crimes of survival,” such as theft for food or supplies, breaking and entering to find shelter, sleeping in public spaces due to homelessness, and drug possession as self-medication. As a result, 2 million people with mental illness are jailed each year. “Once incarcerated, individuals with mental illnesses tend to stay longer in jail and upon release are at a higher risk of returning to incarceration than those without these illnesses…Without change, large numbers of people with mental illnesses will continue to cycle through the criminal justice system, often resulting in tragic outcomes for these individuals and their families, missed opportunities for connections to treatment, inefficient use of funding, and a failure to improve public safety,” explains The Stepping Up Initiative.

Due to the war on drugs, incarceration and criminalization have also been the dominating response to substance use. According to the Drug Policy Alliance, “more than 1.5 million drug arrests are made every year in the US–the overwhelming majority for possession only. Since the 1970s, the drug war has led to unprecedented levels of incarceration and the marginalization of tens of millions of Americans—disproportionately poor people and people of color—while utterly failing to reduce problematic drug use and drug-related harms.” It is thus not a campaign against drugs, but the people who use them.

Further, as noted in the definitions section above, the war on drugs is inherently racist and remains so today in direct and indirect ways. Most recently we saw this with Breonna Taylor, who was unjustly murdered by police as part of a drug raid. Ms. Taylor, though uninvolved with the crimes in question, was still met with the violence integral to the drug war and policing, nonetheless. It is also important to highlight here that people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be fatally shot by police.

As these injustices continue to compile and reinforce each other, this upcoming election provides us an essential opportunity to work toward correcting these long-standing wrongs.

Current Context

Living in a time of unrest, economic uncertainty, and a pandemic means that many folks are struggling. And that means our mental health is struggling too. For people who were already experiencing mental health challenges or those with substance use disorder, this time creates new challenges and new barriers to assistance, causing heightened stress and concerns for safety. According to the CDC, this has manifested in increased anxiety, depression, substance use, and suicidal ideation—disproportionately so for younger adults, People of Color, essential workers, and unpaid adult caregivers. Moreover, a recent study by the Well Being Trust estimates that by 2029 there could be an additional 75,000 “deaths of despair” as a result of the COVID-19 related economic crisis, due to suicide and drug and alcohol use related deaths. Sheltering in place is a public health good, but the associated isolation and uncertainty are also public health concerns to be considered in our response to the pandemic.

This is why it is critical to include both mental health and services for people who use drugs and alcohol in our conversations about our country’s health care access. In terms of advocacy, this looks like expanding access to mental health services, such as requiring insurance coverage for therapy and ensuring affordable, or no cost, mental health services for those who have lost their jobs and their insurance. It also means continuing the trend of offering these services via telehealth and investing to make telehealth services feasible and broadly available. Some people call this the pandemic behind the pandemic.

So many folks are struggling—some with new worry and anxiety, some with long held and now exacerbated depression, and many with a deep sense of uncertainty. The impact of the pandemic will reverberate through this and the next generation, and thus recognizing the unique mental health challenges and needs of this time is an important part of what recovery looks like.

A Faith-Based Response

Jesus reached out to people who were marginalized, to those who were ostracized, and to those who were the outcasts in the eyes of society. Jesus’ compassion and embrace exemplified what His followers ought to do: reach out to the least, the lost and the lonely. The way of Jesus was comfort, not ridicule; it was love, not indifference; it was empathy, not hostility. The way of Jesus is our spiritual calling. - United Church of Christ Mental Health Network. The United Church of Christ believes in advocating for the dignity of every human being and in overturning customs and policies that undermine this belief—particularly for those whom larger society has deemed disposable or unimportant, like those with mental illness and people who use drugs.

The UCC’s Mental Health Network began in 1992 and continues to serve as a way for people to share experiences, resources, and support around mental health. One of their key ministries is to guide and certify UCC communities as Welcoming, Inclusive, Supportive, and Engaged for Mental Health (WISE), a process which helps congregations to become a hospitable place of belonging for those living with mental health challenges and their loved ones. The Center for Faith and Community Health Transformation, a project of CHHSM member Advocate Aurora Health, is a partner organization of this initiative. The Center is also a powerful example of how health and faith communities can collaborate in their healing efforts. For example, the Center’s faith and mental health specialist works with local clergy by offering education and training, monthly consultation, referrals, and partnerships—all at no cost.

The UCC’s Overdose and Drug Use Ministries (ODUM) is a newer project that focuses on supporting local churches to engage in overdose and drug use ministries. Particularly in congregational settings, "drug use is an issue that people are dealing with, but folks are having a hard time articulating it," says ODUM Project Coordinator Erica Poellot. ODUM helps to meet this pressing need through education, harm reduction strategies, and highlighting the intersections of social inequities, stigma, trauma, drug use, faith, and spirituality. UCC members are also part of the broader harm reduction movement working to improve practices and policies. A leader in this effort is Judson Memorial Church which is a co-founding partner of Faith in Harm Reduction, the only program in the country dedicated to mobilizing communities at the intersection of harm reduction and faith-based organizing.

Additionally at the national level, the UCC has made several General Synod resolutions related to mental health and substance use such as: UCC General Synod Resolution Regarding Mental Illness (1995); WISE Congregations Resolution (2015); Dismantling the New Jim Crow (2015); and The Prison Industrial Complex (1997). At the last General Synod, CHHSM sponsored the resolution Recognizing Opioid Addiction as a Public Health Epidemic (2019), which emphasized the disparities and injustices in access to treatment. This emphasis came from the voices of CHHSM member organizations who intimately felt the impact of the opioid crisis, especially those working in children and family services responding to trauma related to incarceration, child-removal, and death. As Valerie Kruger of Every Child’s Hope explained, so many families do not have the funds to pay for the treatment and even if they do, they might not be able to receive it: “By the time their bed is available, the parent has often resumed using in an effort to prevent withdrawal [symptoms].” Other CHHSM organization leaders, like David Weathersby of Bellewood and Brooklawn, also advocated for policies that fund mental health services instead of incarceration as a response to substance use disorder.

Several other CHHSM organizations provide direct service in these specialty areas as well. In January 2020, the Salam Clinic—a free health clinic run in partnership by local congregations, Deaconess Nurse Ministry, and physicians from the Islamic Foundation of St. Louis, MO—expanded their services to include mental health care, filling a major gap for the uninsured and underinsured in their area. Outside of the clinical setting, organizations working in transitional housing are also making a difference by providing multiple services in one place. In addition to safe and confidential housing, Lydia’s House and The UCC Transition House offer mental health services to survivors of domestic violence to support their healing process. The transitional housing program through Champ Homes specializes in supporting those who are experiencing both homelessness and a mental health diagnosis. And the Cooper House program at Doorways serves people who are unable to live independently as a result of HIV/AIDS—one of the first programs of its kind in the country. An integral part of their work is to provide mental health and disability services for their residents, which has been shown to reduce barriers to receiving care and increases maintenance of their HIV/AIDS treatment.

Questions for Candidates

- In what ways will you ensure that everyone will have access to mental health care? How are you working to destigmatize mental health coverage and to make sure that care is not reserved just for those who can pay out of pocket?

- In what ways will you remove barriers to substance use treatment and harm reduction services?

- The pandemic has caused a lot of people to lose their jobs, which means they’re losing their insurance as well. What plans do you have for bolstering programs to help those who are uninsured access mental health services?

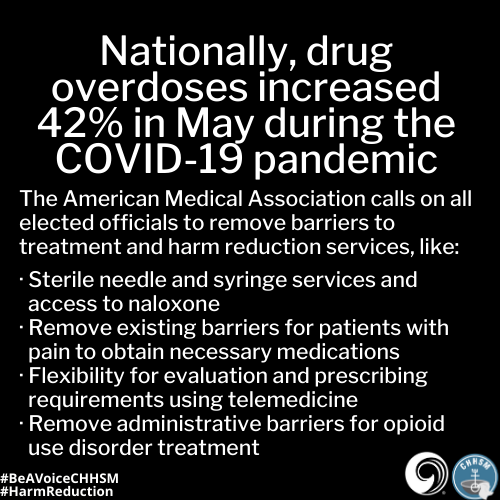

- Often overlooked, substance use treatment and harm reduction services need increased funding, particularly now as use, overdose, and deaths from overdose have risen during the pandemic. How will you develop policies that are equitable and not based on a punitive model of care?

Social Media Samples

You can find the below graphics and more by following CHHSM and JWM on social media.

Follow the UCC’s Council for Health and Human Service Ministries (CHHSM) at:

Follow the UCC’s Justice and Witness Ministries (JWM) at:

More Information

For more on mental health, substance use, and harm reduction, check out these resources:

- Mental Health Advocacy by the Disability Visibility Podcast

- Policy Issues for 2020 by #Vote4MentalHealth

- Racial Trauma is Real: Resource Guide by Institute for the Study and Promotion of Race and Culture

- Between Sessions Podcast by Melanin and Mental Health

- Radical Syllabus by the National Queer & Trans Therapists of Color Network

- Justin Michael Williams on Staying Woke by The Good Ancestor Podcast

- The Stepping Up Toolkit by The Stepping Up Initiative

- Spirit of Harm Reduction: A Toolkit for Communities of Faith Facing Overdose by Faith in Harm Reduction

- Transformative Justice Handbook by Generation Five

- Getting Naloxone in Your State by NEXT Distro

- Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction Myths and Fact by the Legal Action Center

- Congregational Action Toolkit to Stop Relying on Police by SURJ-Faith

- When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir Discussion Guide

- Live Another Day

COVID-19 and Mental Health and Substance Use

The spread of the COVID-19 virus has caused changes in access to care and services related to mental health and substance use. Below are some relevant resources that are specific to COVID-19.

- Mental Health and COVID-19 Information and Resources by Mental Health America

- COVID-19 Guidance for People Who Use Drugs and Harm Reduction Programs by the National Harm Reduction Coalition

Where to Find Us

Please visit our websites to learn more about CHHSM and JWM.