CHHSM Advocacy Center

Vol. 7: Services to Persons with Disabilities

Tracy and Katrina’s Story

Tracy and Katrina

(Image description: a picture of two women smiling next to each other. Katrina is seated on the right wearing a yellow tank-top and Tracy, wearing a red t-shirt, is standing slightly behind her on the left with her arms around Katrina. They are outside on a sunny day in front of a red brick building.)

“Katrina is family. When I can see I’m making a difference in others, my heart is filled with joy. At the end of the day, I know I’m making a difference in her life and I feel great that I can help Katrina. I know this job is a gift from God,” says Tracy, a Direct Support Professional (DSP) at CHHSM member organization Emmaus Homes in St. Louis, MO. Founded in 1893, Emmaus Homes provides around-the-clock support services to people with cognitive or developmental disabilities. It is not uncommon that meaningful relationships are often formed between their team members and clients, much like the bond shared between Katrina and Tracy.

Just over 4 years ago, Katrina made the decision to move out of her natural home. After choosing Emmaus and her roommates, she met Tracy, one of the Direct Support Professionals who works with Katrina. Their connection was instant.

In Katrina’s initial meeting with her care team, they worked together to create an Individualized Support Plan. The plan focuses on Katrina’s goals to become more independent in areas like household chores, education and recreation. Achieving these goals brings a tremendous sense of pride for both Katrina and Tracy. Earlier this year, Katrina shared her new goal with Tracy–to get a job. Tracy found a volunteer opportunity that would give Katrina the skills she needed. Katrina now volunteers two days a week at Goodwill, stocking and pricing items. While her co-workers assist her, Tracy is also there for support. Katrina has become a popular volunteer and has many customers who stop by just to see her.

Tracy feels rewarded that she is making an impact in Katrina’s life. But in much the same way, Katrina has impacted Tracy’s life, too. Tracy has a child with similar disabilities and her training at Emmaus allows her to utilize many of the skills she’s learned from her work with Katrina.

Given the difference professionals like Tracy have on a person’s life, it is essential to support them, in turn, to continue to do so. Unfortunately, there is a real DSP workforce crisis in this country due to lack of funding. Government rates for their services are simply too low to hire and retain staff consistently. Thus, solving the DSP workforce crisis has become the top legislative priority at Emmaus Homes. As their website states, “We believe everyone deserves the resources to live independently. The problem is that services for people with disabilities are underfunded and understaffed.” Yet, despite systemic disinvestment of disability services at the state level, the Emmaus Homes Board of Directors made the bold decision to invest $10 million over the course of three years to help retain the high-quality staff at Emmaus. As our faith calls us to be a voice with persons with disabilities, so too does it call us to advocate for those who support them.

To read more about Tracy and Katrina and to view a video interview, click here.

Definitions

Particularly coming from a social justice perspective, discussing disability advocacy requires understanding the broad range of issues involved and the diversity of perspectives and language used. To provide a foundation for this conversation, below are some definitions from a variety of sources committed to this work.

- Disability Justice: A movement and framework which addresses the multitude of ways disability and ableism intersect with other forms of oppression and identities (e.g. Black, Indigenous, People of Color, queer, trans, immigrant, poor, homeless, incarcerated, etc.) and centers on the lived experiences of those intersecting identities to work for social change and liberation. Conceived by queer disabled women of color Patty Berne, Mia Mingus, and Stacey Milbern in 2005, and later joined by many others, Disability Justice grew out of a critique of the disability rights movement as overly focused on the perspectives of straight white men with physical disabilities. It recognizes the intersecting oppressive systems of white supremacy, colonial capitalism, homophobia, sexism, ableism, etc. in understanding how peoples’ bodies and minds are valued or how they are labeled as “deviant,” “unproductive,” and “disposable.” Disability Justice believes that all bodies and minds are unique, essential, and have needs that should be met.Further, while improving the legal rights of disabled people has been and continues to be vital, Disability Justice emphasizes a broader examination of the root causes of inequities. As Mia Mingus explains, “Disability justice is a multi-issue political understanding of disability and ableism, moving away from a rights-based equality model and beyond just access, to a framework that centers justice and wholeness for all disabled people and communities.” To learn more about the 10 Principles of Disability Justice, click here.

- Ableism: A system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, excellence and productivity. These constructed ideas are deeply rooted in racism, anti-Blackness, eugenics, colonialism, and capitalism. This form of systemic oppression leads to people and society determining who is valuable and worthy based on a person’s appearance and/or their ability to satisfactorily [re]produce, excel, and "behave." You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism.

- Social Model of Disability: A framework for understanding disability as caused by the attitudes and structures of society and not by one’s medical condition. It is a civil rights approach to disability, which proposes that people with disabilities would not experience exclusion or barriers if modern life were structured around accessibility and inclusion. This approach contrasts with the medical model, which sees disability as caused by a person’s health condition. Some argue that in the medical model, everyone would need a non-disabled body and mind to participate fully in society.Further, the social model makes an important distinction between impairment and disability. Impairment is simply the state of the body or mind that is “non-standard,” which may be understood to be negative, positive, or neutral by the person living with the impairment. Disability, rather, is the disadvantage or restriction of activity and engagement one experiences due to ableist norms and structures.

- Neurodiversity: a concept that recognizes and respects neurological differences as any other human variation. These differences can include those labeled with Dyslexia, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Autistic Spectrum, Tourette Syndrome, and others. Coined in the late 1990s by Autistic sociologist Judy Singer, it critiques the prevailing view of neurodiversity as inherently pathological. The neurodiversity movement challenges society to rethink these diagnoses through the lens of human diversity, proposing to value the variations in neurobiologic development in a similar way to how we value diversity in gender, race, ethnicity, religion, etc. As opposed to only focusing on impairments, the neurodiversity model emphasizes how individuals have a complex combination of cognitive strengths and challenges.

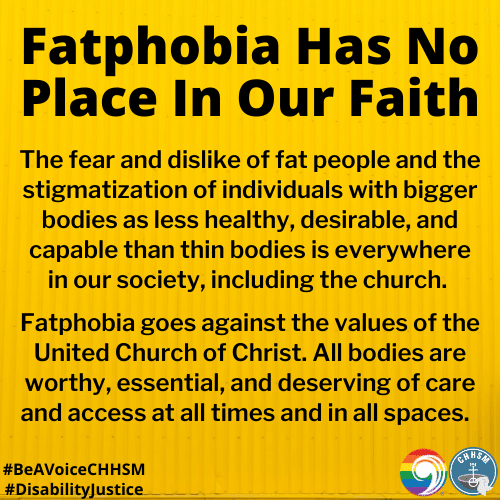

- Fatphobia: the fear and dislike of fat people and the stigmatization of individuals with bigger bodies as less healthy, desirable, and capable than thin bodies. Institutional fatphobia perpetuates the idea that one must be a certain size to be deserving of care and access. It is embedded in the ways fat people’s lives are over-determined by systems and structures, such as the diet industry, the media industry, public standard-size seats and turnstiles, standard-size clothing, etc. Anti-fat bias is often discussed with language of concern for a fat person’s health, yet neither obesity nor thinness is necessarily a complete or accurate indicator of someone’s health. For example, when “obese” people are “metabolically fit”– that is, active and physically well–their risk of heart disease and cancer are no greater than non-obese people. Fatphobia resembles ableism because they are rooted in similar oppressive principles: (1) the lives of people in socially valorized bodies are more valuable than those of people in marginalized bodies and (2) living in a marginalized body is presumed to be inherently undesirable. Fat people, with and without disabilities, also face immense discrimination and lower quality of care within the health system, and these issues have only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

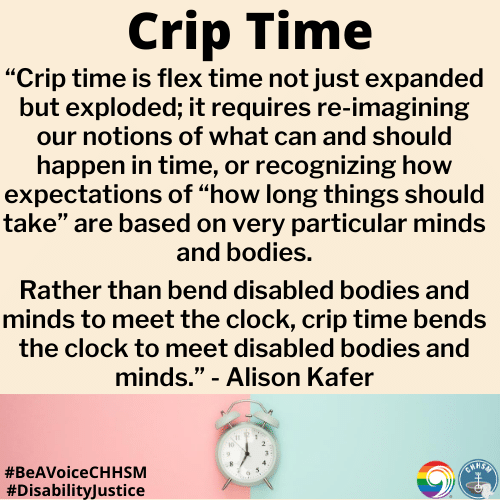

- Crip: an in-group slang word for people with disabilities. It is considered to be an inclusive term, representing all people with physical, psychological, and/or neurological differences and disabilities. The term Crip within the disability community reflects the positive political reclaiming of the historically derogatory term “cripple,” which not only diminished the person’s dignity but also excluded those with non-physical disabilities from the disability community.

- Access: needs that are required for someone to fully participate in a space or activity, which can include wheelchair access, scent-free space, ASL interpretation, etc. In a Disability Justice context, access needs are seen as universal. Everyone has needs of the body-mind, not just disabled people, and those needs can also change throughout one’s lifetime. Thus, the goal of access is not assimilation, but rather deeper connection and breaking down isolation for everyone, at all times and in all spaces.

- Self-determination: the opportunity and support to make choices and decisions about one’s life. Historically, many individuals with intellectual and/or developmental (I/DD) disabilities have been denied their right to self-determination. They have often been overprotected and involuntarily segregated, with others making decisions about key elements of their lives. Yet the right to self-determination exists regardless of guardianship status. Family members, friends, and other allies can play a critical role in promoting self-determination by providing support and working collaboratively to achieve an individual’s goals.

- Supported-Decision Making (SDM): a tool that allows people with disabilities to retain their decision-making capacity by choosing supporters to help them make choices. A person using SDM selects trusted advisors, such as friends, family members, and/or professionals to serve as supporters. The supporters agree to help the person with a disability understand, consider, and communicate decisions, giving the person with a disability the tools to make their own informed decisions. This is different than a health care power of attorney, who acts as the surrogate decision-maker if a person becomes incapacitated.

- Medical Triage: the process of sorting people based on their need for immediate medical treatment as compared to their chance of benefiting from such care. Triage is typically done in emergency rooms, disasters, and wars, when limited medical resources must be allocated to maximize the number of survivors.Serious concerns and formal complaints have been made by disability activists over discrimination in medical triage for COVID-19 treatment, as certain institutions and governing bodies have used criteria that deprioritize people with disabilities. Activists note the underlying belief in these criteria is the lives of people with disabilities hold less value because their quality of life is presumed to be less–an assumption that could be made without including the patient’s own wishes and values. For example, an earlier version of Alabama’s Emergency Operations Plan would deny ventilators to people based on their status as having severe or profound intellectual disabilities. These guidelines have since been removed after a complaint was filed with the Department of Health and Human Services and the Office for Civil Rights.To learn more about how the lives of people with disabilities are being protected and advocated for during this pandemic, see the COVID-19 Resources section of this toolkit.

Background Information

July 26, 2020 marked the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a landmark piece of legislation banning discrimination on the basis of disability in the areas of employment, public accommodation, public services, transportation, and telecommunications. Like other forms of civil rights legislation, the ADA was long overdue to correct and reconcile with systemic oppression in the United States. Of particular note were the policies guided by Social Darwinism and the Eugenics movement in the early 20th century, which led to segregation in housing and education, forced sterilization, marriage prohibition, incarceration, and institutionalization of disabled people.

The persistent work of grassroots disability activists to get the ADA and its predecessor bills passed cannot be overstated. The longest sit-in at a federal building to date is the 504 Sit-in held in the San Francisco Department of Health, Education, and Welfare building in 1977. Organized by Judy Heumann and Brad Lomax, the sit-in demanded Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act be enforced, which prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities in programs that receive federal funding. The demonstration lasted 28 days with over 100 participants, most of whom were people with disabilities. Because of Lomax, it was also supported by the Black Panther Party, who provided food, transportation, media coverage, and care. Lomax, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis while in college, saw that people with disabilities were regularly denied an education, and that there were few services to help them find housing or jobs, especially if they were Black. He was an instrumental voice in bringing awareness to the intersections of racial and disability justice.

The sit-in laid the groundwork for the policies in ADA, as well as the method to make it happen. When the ADA seemed destined to be stalled in Congress, disability rights group ADAPT held a march from the White House to the steps of the Capitol. Sixty disability activists with physical disabilities left behind their crutches, wheelchairs, and other assistive devices and crawled up all 78 steps of the Capitol. It gave a dramatic demonstration of how inaccessible public spaces and architecture are. The “Capital Crawl,” as it would become to be known, pushed the ADA bill out of committee and was signed into law by George H. W Bush in 1990.

Yet the fight for disability justice did not end with the ADA, with ableist norms, policy pushback, and underfunding persisting, all while one in four Americans live with a disability. If people with disabilities were a formally recognized minority group, they would be the largest minority group in the country. Moreover, like all the issues raised in this toolkit, disability advocacy must be centered on intersections such as these:

- People of color make up the majority of people with disabilities, even though White people with disabilities are more often represented in the media;

- People who are poor and have low-education have disabilities at disproportionate rates;

- Incarcerated people are three to four times more likely to have a disability;

- Chronic pain, the leading cause of disability in the US, disproportionately affects women, yet they are less likely to receive pain treatment than men, and Black patients’ pain is taken less seriously regardless of gender;

- Post-9/11 active-duty veterans have disability rates significantly higher than those of previous generations, with 41 percent of those who served after 9/11 having a disability compared to 25 percent of veterans of other eras;

- Non-elderly adults with disabilities who rely on Supplemental Security Income (SSI) are among the groups most severely affected by the extreme shortage of affordable rental housing across the country, leading to homelessness, institutionalization, incarceration, substandard housing, or severe rent burdens–sometimes accounting for 100% of their SSI.

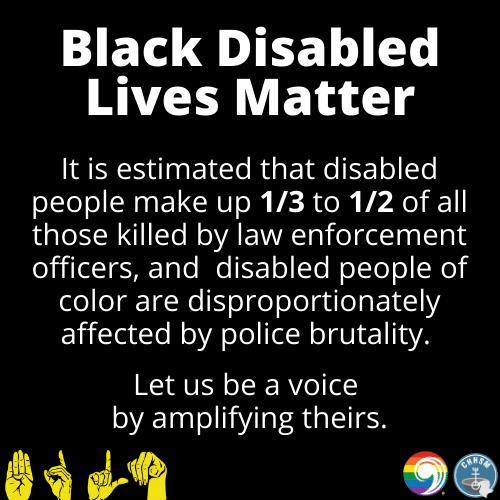

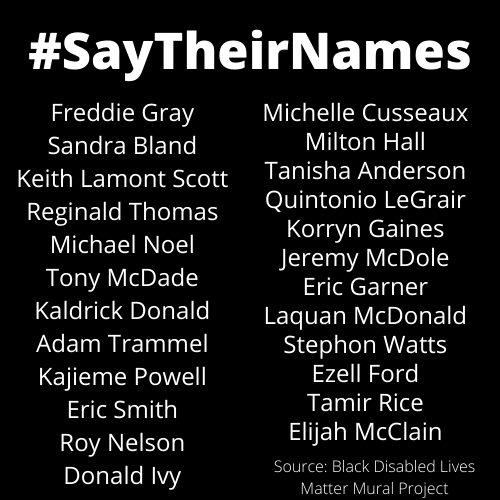

Finally, as another social uprising has sparked across the country in response to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and the thousands who died before them, it is crucial to highlight the ways in which police brutality impacts the lives of people with disabilities. Although there is no definitive recording of the disability status of those killed by police, the Ruderman Family Foundation published a 2016 study that estimates disabled people make up a third to half of all those killed by law enforcement officers. It is also estimated that the risk of being killed during a police incident is 16 times greater for individuals with untreated serious mental illness.

(Content notice for the stories below: gun violence, killing by police)

This is especially alarming when those who call police specifically asking for help for themselves or others are also met with violence, as the tragic deaths of Kayden Clarke and Stephon Watts exemplify. Clarke, a white Autistic transgender man who was seeking transition-related medical care had just been told he was denied hormone therapy due to his Autism diagnosis. Neighbors called the police out of concern that Clarke was at risk for suicide; but rather than trying to calm and assist him, the officers “drew and pointed their guns in the dark and shouted demands, terrifying [Clarke].” The police reported Clarke had a knife and walked towards them. They then shot him, and he died later that night. Similarly, Watts, a Black Autistic 15-year-old, was experiencing emotional distress because he did not want to go to school. Per advice from the hospital and social worker, Watts’ father called the police for assistance. Watts had calmed down prior to their arrival, but the four officers insisted on checking the house. When they found Watts in the basement, an officer saw him with a butter-knife, yelled “Knife!”, and then two officers shot and killed him.

These stories and statistics are disturbing, and the need for deeper understanding on these issues is greater than ever. To address this, #BlackDisabledLivesMatter has created a platform to bring awareness of how the lives of disabled people of color are disproportionately affected by police brutality. The movement provides education and avenues for solidarity in the work for healing and justice. At this pivotal time in history, let us all join in and continue to show up for change in our country.

Current Context

As with everything, the COVID-19 crisis highlights the inequities inherent in our society. Protections for those with disabilities need to be included as we map out how to navigate both the public health crisis, and the resultant economic crisis. These include investments in home and community-based services for those with disabilities and increased funding for Medicaid and coverage of the state-share for Medicaid to continue much needed care services. The essential health care and supports for people with disabilities should be recognized as such, by classifying those who provide direct support as essential workers.

There is a critical and fundamental shift in thinking about people with disabilities that needs to be made in the legislative and policy space. There is a misguided understanding of what an individual’s contribution to society is, which have led to discriminatory metrics to determine that value. We see it most glaringly in the provision of care for people with COVID and how some health systems classify who should receive lifesaving treatment. But it is an insidious thread in the rest of society including discriminatory hiring and pay practices. Someone with a disability is twice as likely to live in poverty and be unemployed. Those rates are even higher for people living with a disability who are Black or Native. We need to establish more inclusive economic protections and rules that make sure that people can get jobs, get paid a fair wage, and receive inclusive job training and education. This lack of ability to build economic security means that people face a much higher rate of poverty and homelessness.

Oftentimes disability rights are relegated to the back burner, which is shortsighted on everyone’s part because of how many people have or care about someone with a disability. All of us benefit if we use a universal design approach to legislating and policy making. Congress has not passed another COVID relief package yet and as candidates campaign, we have an opportunity to highlight some of the significant issues facing the disability community.

A Faith-Based Response

So God created humankind in God’s image. In the image of God, God created them. (Gen. 1:27). The United Church of Christ envisions a world in which all people are included in the fullness of life because they are created in the image of God. Since the 1970s, issues of disability rights, inclusion, and justice have been an important ministerial focus for the denomination. Perhaps most notably, Rev. Harold Wilke provided early leadership in examining the ways in which a truly caring congregation is an accessible one. In his book Creating the Caring Congregation, he discussed accessibility and inclusion from perspectives of both architecture and spirituality. Wilke was also present for the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act and offered the Invocation at the White House ceremony, saying that the new law was "the breaking of the chains which have held back millions of Americans with disabilities."

Over the past several decades, numerous General Synod Resolutions have been passed on disability justice such as becoming a church accessible to all, dismantling discrimination in mass incarceration, and support for voting accessibility for people with disabilities, to list a few. One of the most recent resolutions from 2017 calls for continued movement towards disability justice by prodding “the church to do more, aside from charity, to speak with a prophetic voice on the need for justice in the lives of people with disabilities.” It names important issues like police brutality, access to public education, fair wages and unemployment, health disparities, disaster preparedness, and the US’s lack of support of the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities.

Additionally on the national level, the United Church of Christ Disabilities Ministries provides education, conferences like Widening the Welcome, spirituality resources, and leadership from people with disabilities and allies. It also supports UCC congregations and organizations to become designated as A2A (Accessible to All). A2A signifies a commitment to be physically and attitudinally welcoming of people with disabilities. One of the unique and important aspects of the A2A designation is to “opt in” to compliance with the ADA. It may come as a surprise for some to know that religious entities are exempt from Title III of the ADA, regarding “places of public accommodation.” This exemption can impact clergy, congregants, and guests alike.

Lastly, CHHSM member organizations have been involved in direct services, housing, and health care to persons with disabilities since the late 19th century. For example, Peppermint Ridge provides housing, nursing, support and nutritional services, and 1:1 coaching to their residents–all of which creates an inclusive environment for self-determination and dignity. Other agencies, like Retirement Housing Foundation expanded their mission to include housing for persons with disabilities as part of their faith-based values, and Earl’s Place opened a permanent housing program for men who have been chronically homeless and have a disability in 2015.

Questions for Candidates

- Do you support a minimum wage of $15 for all workers, including those with disabilities? How do you propose to protect people living with a disability from discriminatory economic practices?

- Explain your plan to fix the structural barriers in Social Security so that people with disabilities are not caught in a poverty trap?

- What educational plans do you have to improve public education access for students with disabilities?

- People living with disabilities face a disproportional incidence of violence from law enforcement and incarceration. What steps will you take to reduce these incidents and break down the systemic barriers that cause this?

Social Media Samples

You can find the below graphics and more by following CHHSM and JWM on social media.

Follow the UCC’s Council for Health and Human Service Ministries (CHHSM) at:

Follow the UCC’s Justice and Witness Ministries (JWM) at:

More Information

For more information on services to persons with disabilities and disability justice, check out these resources:

- Multisensory Worship Ideas by The UCC Disabilities Ministries

- Is God Inaccessible? (feat. Zaynab Shahar) by the Power Not Pity Podcast

- Information on 2020 Presidential Candidates by the AAPD & #CripTheVote

- Advocacy Priorities and Talking Points Guide (2020) by the National Council of Independent Living

- ADA 30 in Color by the Disability Visibility Project

- Disability Justice Toolkit by Showing Up for Racial Justice

- Ableist Words and Terms to Avoid by Autistic Hoyat

- Documentary Recommendations from Deaf and Disabled People by the Disability Visibility Project

- Aging and Disability: Beyond Stereotypes to Inclusion by The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

- America’s Direct Support Workforce Crisis: Effects on People with Intellectual Disabilities, Families, Communities and the U.S. Economy by the President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities

COVID-19 Resources

The spread of the COVID-19 virus has caused changes and increased precautions for everyone; and services to support those with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to its impact. Below are some relevant resources that are specific to COVID-19.

- Know Your Rights Guide to Surviving COVID-19 Triage Protocols by NoBody is Disposable Coalition

- Ensuring Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities During COVID-19 Webinar by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University

- The Impact of COVID-19 on Disabled People: An Interview with Bioethicist Joe Stramondo by the Disability Visibility Podcast

- Coronavirus and Spirituality: An Interview with Rabbi Elliot Kukla by the Disability Visibility Podcast

- Organizing in a Pandemic: Disability Justice Wisdom by the Irresistible Podcast

CHHSM Organizations Providing Services to Persons with Disabilities

There are many more CHHSM members not included in this list who also support people with disabilities by providing affordable housing, emergency shelter care, and primary and acute care. We are proud of the multitude of ways CHHSM members support people holistically.

Where to Find Us

Please visit our websites to learn more about CHHSM and JWM.