CHHSM Advocacy Center

Vol. 3: Reproductive Health Care

Essence's Story

Photo credit: Gabrielle Muller,

courtesy of Yale Divinity School

“Personally, I have found myself deeply invested in exploring how the church can act as a better advocate for folx* who need reproductive health benefits and education,” says Essence Ellis, MDiv candidate at Yale Divinity School and the Rev. Jerry Paul CHHSM Scholar. “Often, when we think of reproductive health care, our minds drift to conversations of abortion and birth control–while both are prominent topics in the reproductive health care conversation, there are many more aspects to consider.” According to The World Health Organization, reproductive health “implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so.” Essence believes the comprehensiveness of this definition is what makes it accessible for all who feel called to participate in the reproductive health conversation.

Recently Essence has been volunteering at the Stetson Library in New Haven, which serves as a space for the local community to gather and learn about a variety of issues. In the fall of 2019, she gave a presentation on the importance of bringing light to reproductive health in minority communities. Reflecting on that experience Essence says, “While participation in the initial presentation was tense, many women felt comfortable coming up to me afterwards to express their interest in holding space for conversations on sexual wellness. For me, it was deeply inspiring to know that this topic holds importance for other Black women and that in the moment, the women in that space felt safe talking to me about it.”

Because of the program’s success, Essence has begun working with Diane Brown, the library’s branch manager, to curate sexual health programming for local women and children. For this initiative they will be using the comprehensive sexuality education curricula Our Whole Lives, developed by the UCC and the Unitarian Universalist Association. “Of course, reproductive health advocacy will be different for everyone, but if we all use our time and resources intentionally, major strides can be made in the journey towards equitable, inclusive, and fulfilling reproductive health for all,” concludes Essence.

Learn more about the Rev. Jerry Paul CHHSM Scholar Program.

* folx: is a gender-neutral collective noun used to address a group of people. Unlike the term "folks," the ending "-x" on "folx" specifically includes LGBTQIA+ people and those who do not identify within the gender binary.

Definitions

Particularly coming from a social justice perspective, discussing reproductive health care can encompass a broad range of issues. To provide a foundation for this conversation, below are some helpful definitions from Queering Reproductive Justice: A Mini Toolkit—one of the resources listed in the ‘More Information’ section.

- Reproductive Health (“RH”) focuses on the provision of healthcare services, health facilities, research, and a person’s relationship with their provider. Particular attention is paid to expanding access to preventative care and culturally competent services. It includes different methods of birth control, fertility methods, abortion, and pregnancy.

- Reproductive Rights (“RR”) is an approach that centers and protects a person’s legal rights to reproductive healthcare services, particularly the right to have an abortion, use birth control, and have affordable healthcare, adequate prenatal and pregnancy care, and sex education that is comprehensive and LGBTQ-inclusive. RR work is focused on administrative policy, legislation, and judicial decisions, at both the federal and state levels.

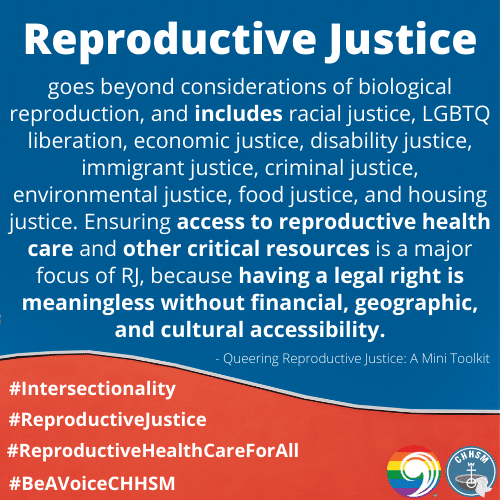

- Reproductive Justice (“RJ”) merges reproductive rights and social justice and it does so through a human rights framework. RJ goes beyond considerations of biological reproduction and includes racial justice, LGBTQ liberation, economic justice, disability justice, immigrant justice, criminal justice, environmental justice, food justice, and housing justice. Ensuring access to reproductive healthcare and other critical resources is a major focus of RJ because having a legal right is meaningless without financial, geographic, and cultural accessibility.The term “reproductive justice” was coined in 1994 by Black women in order to center the experiences and needs of Black women. Because the mainstream pro-choice movement did not meet the needs and lived experiences of women of color, Black women created their own space and movement. Adopting human rights, social justice and reproductive rights tenets, these women created a transformational and grassroots-based movement and framework. While the term was officially coined in 1994, women of color, including indigenous women, and LGBTQ individuals, particularly trans women, have been leading the struggle for reproductive equality and liberation for centuries. Reproductive justice will be achieved when all people have the ability to determine if, when and how to not have a child, to have a child and to parent the children that they have in safe and healthy environments. Reproductive justice also includes access to gender-affirming care for all people.

Background Information

According to the United Nations, reproductive health is considered to be a human right and fundamental to a person’s self-determination and autonomy. As such, it is the government’s responsibility to ensure conditions to support a healthy reproductive life, including access to health care facilities, sufficient quality and quantity of services available to all, and culturally competent care. Yet even though the United States is one of the wealthiest nations in the world, we have a long way to go in fulfilling this responsibility.

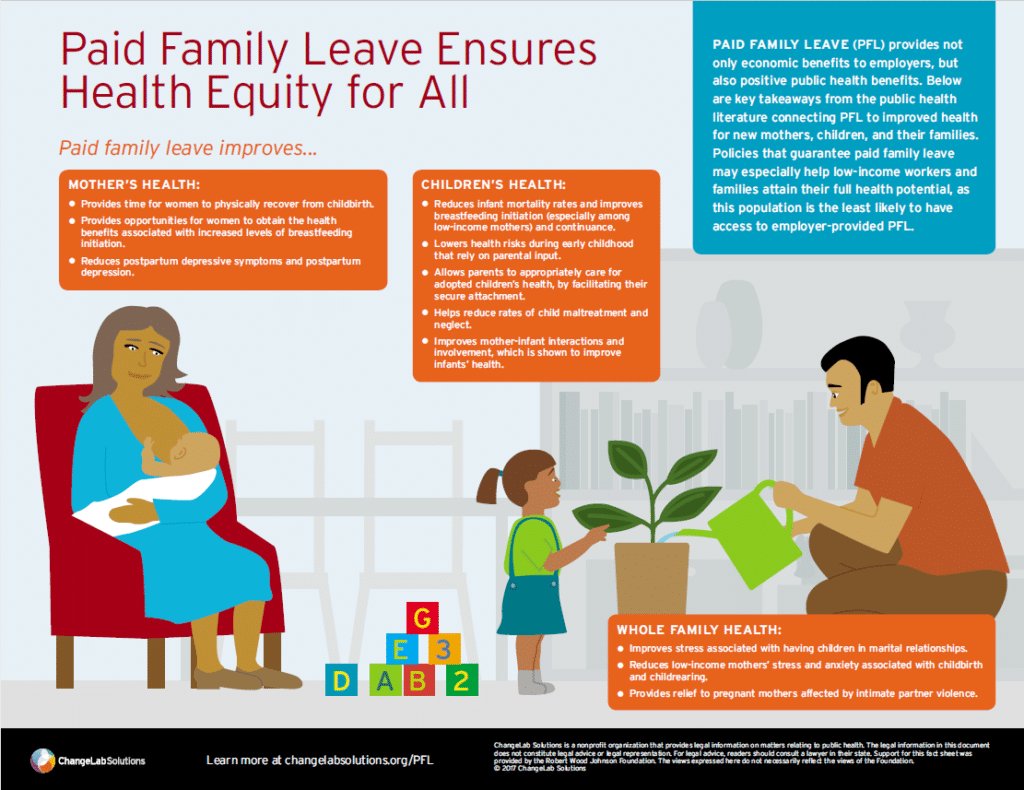

Perhaps the most striking illustration of the work ahead is the current state of pregnancy health and services. According to the World Health Organization the US is one of only 13 countries worldwide with a rising maternal mortality ratio, and is the only economically developed country on that list. Moreover, Black women are three-to-four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes, many of which are preventable with access to affordable and culturally competent care, than White women. The US is also one of the only countries in the world to not have mandated paid parental leave. For those wanting to end a pregnancy, over the past 40 years the Hyde Amendment has prohibited abortion services to be covered for those under Medicaid (except in cases of rape, incest, or life endangerment), in federal prisons and detention centers, in the military, enrolled in CHIP, and for Native Americans. Thus, low-income and women of color have continued to disproportionately face barriers to receiving abortion care and are more likely to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term.

Pregnancy prevention services are also in need of greater support. Publicly funded “safety-net” health centers are essential to providing contraception access, STD/I testing and treatment, etc. for many people, particularly for low-income and adolescent women. However, research indicates the need for publicly subsidized services exceeds the level of support that is provided, and numerous states have attempted to shut down or defund certain providers, like Planned Parenthood, even in areas with limited health care options or infrastructure.

Finally, as illustrated in Essence’s story, sexuality education is vital to reproductive health; yet comprehensive information and counseling is lacking in many communities. One of the reasons for this is because sexuality education is largely directed by local, district, or school officials, and thus content varies substantially from state to state. Further, only 24 states mandate public schools to teach sexuality education, just 18 of them include contraception information, and a mere 13 require the information to be medically accurate.

Current Context

As millions of Americans remain uninsured or underinsured, advocating for reproductive health must start with the basics of health care for all, and with coverage that is comprehensive. Currently reimbursement for births can vary widely under different plans, sometimes with thousands of dollars remaining for the patient to pay, and not all reproductive health services are covered by insurance, as in the case of abortion. Moreover, in recent years many state and local public health budgets have been substantially reduced, hampering health departments’ ability to address maternal health. Increasing state funding to programs like the Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grants are essential to reducing maternal and infant mortality.

Last year saw a wave of state-level actions to limit reproductive health care coverage by placing restrictions on access to abortion. Alabama passed one of the most restrictive measures against abortion in the nation. In March 2020 the Supreme Court took up a challenge to a Louisiana law that would require doctors performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic. This would leave a state of 4.5 million residents with access to only one abortion provider. A second wave of state-level restrictions on abortion access is likely this year. Last year, several members of Congress introduced the Women’s Health Protection Act which would serve as a federal safeguard against restrictive state laws.

The current Administration has attacked access to the full range of reproductive care on a number of fronts. The reinstatement of the global gag rule blocks U.S. global assistance to international health providers who provide counsel on the full range of reproductive health care options, effectively cutting off funds for agencies that also provide contraception, prevention and treatment for HIV/AIDS, malaria treatment and maternal child health. The domestic gag rule similarly restricts funding to health care providers in the U.S. who provide access to abortion care. The Administration has also acted aggressively to appoint federal judges who favor restrictions if not an all-out ban on abortions. In Congress, conservative lawmakers repeatedly attempt to introduce restrictive measures on access to the full range of reproductive health care. Repeated attempts to undermine the Affordable Care Act also undermine women’s access to the full range of health care.

Finally, because reproductive health does not start, or end, with pregnancy, we also need comprehensive, evidenced-based sexuality education for all our youth and to address the socio-economic conditions that impact reproductive health and choices with policies that support stable thriving communities.

A Faith-Based Response

The United Church of Christ supports safe, affordable, accessible, and culturally competent reproductive health care for all and has been committed to reproductive justice since the 1960’s. Before the U.S. Supreme Court's historic decision in Roe v. Wade in 1973, a network of clergy emerged to help connect women seeking an abortion with doctors who could safely provide them. Made up of Protestant ministers, Jewish rabbis, and dissident Catholic nuns and priests, the Clergy Consultation Service announced their services on May 22, 1967. Several UCC clergy were involved in launching the network, and several more joined it over the years. Its successor, the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, was founded by diverse groups, including the UCC’s national ministries.

Further, since 1971 there have been eight General Synod Resolutions on freedom of choice, family planning, and reproductive health. These resolutions speak to a theological understanding that all persons have a God-given right to moral agency, autonomy, and self-determination, and how our religious heritage compels us to create environments where people can come to understand and respond to the joys and challenges facing them as sexual beings. Currently the UCC’s involvement in reproductive justice continues to be multifaceted through advocacy, education, community work, and providing health care in UCC affiliated medical facilities.

For example, the UCC spoke out strongly for the requirement of insurance plans to cover services such as contraception, breast feeding support, domestic violence screening, and HIV & STI counseling when for-profit businesses claimed that the contraceptive mandate in the ACA was a violation of their religious liberty; and UCC leaders and ministers continue to advocate at events like Stop the Bans rallies and to provide spiritual support to reproductive health centers.

In collaboration with the Unitarian Universalist Association, the UCC has created faith-based sexuality education programs such as Our Whole Lives and Sexuality and Our Faith. And CHHSM member Advocate Aurora Health not only offers comprehensive women’s health and fertility services, since 1996 they have provided school-based health centers to underserved adolescents. These teens face multiple barriers to receiving reproductive health care, in particular, and are able to access services regardless of ability to pay.

The UCC remains on the frontlines of achieving equity and justice for reproductive health and the 2020 election will be an important opportunity to be part of that movement for positive change.

Questions for Candidates

- More and more women’s health care clinics face closure due to restrictive state measures on access to abortion. These clinics also provide a wide range of health care for women, including cancer screenings and prenatal care. What would you do to ensure that women can receive the full range of health care, including reproductive health care?

- Women of color face far greater obstacles to the full range of reproductive health care. One consequence is a higher rate of maternal deaths. How would you address this?

- What is your position on the Hyde Amendment?

- What steps would you take to empower women to access the full range of health care and protect their autonomy to make the decisions they deem best for their health and the health of their families?

Social Media Samples

- Advocating for paid parental, sick, and family leave policies is advocating for reproductive health. Research shows that paid leave improves the mental and physical health of birthing persons, reduces infant mortality, and positively impacts public health overall. In 2020, let’s advocate for #ReproductiveHealthCareForAll and the range of policies that support it.

Follow the UCC’s Council for Health and Human Service Ministries (CHHSM) at:

Follow the UCC’s Justice and Witness Ministries (JWM) at:

More Information

For more on reproductive health care and reproductive justice, check out these resources:

- The Intersection of Faith and the Hyde Amendment by Religious Institute

- Worship Resources for Reproductive Justice by Religious Institute

- Queering Reproductive Justice: A Mini Toolkit by National LGBTQ Taskforce

- Black Mamas Matter: Advancing the Human Right to Safe and Respectful Maternal Health Care by Black Mamas Matter Alliance and the Center for Reproductive Rights

- Reproductive Justice and Sexual Violence: Making Connections by Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs

COVID-19 and Reproductive Health

The spread of the COVID-19 virus has caused changes and increased precautions for everyone; and reproductive and sexual health are no exception to its impact. Below are some relevant resources that are specific to COVID-19 and reproductive health.

- Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Breastfeeding Recommendations

- Information on Reproductive and Sexual Health Telemedicine Services

- Information on Reproductive Rights and Potential Barriers to Care

- Harm Reduction Recommendations for Those Involved in Sex Work

(See Presentation Slide #21 and the Webinar Notes, in particular) - Information for Those with HIV

Where to Find Us

Please visit our websites to learn more about CHHSM and JWM.